- Home

- Ricardo Sanchez

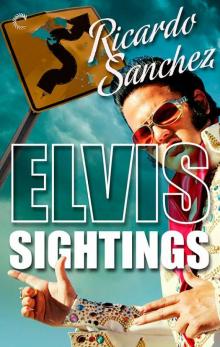

Elvis Sightings (An Elvis Sightings Mystery) Page 2

Elvis Sightings (An Elvis Sightings Mystery) Read online

Page 2

It was a dull drive filled with sagebrush and dirt, so my thoughts quickly turned to Buddy. He probably knows more about Elvis than Elvis does, and over the years he’d turned all that trivia into a philosophy rooted in the words and deeds of the King. Buddy has an Elvis quote for just about any situation, but his favorite is “Do what’s right for you as long as it don’t hurt no one,” a motto I’ve taken to heart. It’s because of Buddy that I’m a Lifestyle Elvis. There aren’t a lot of us, but it’s a growing movement, getting bigger every year. Most Lifestylers channel their inner Elvis privately, but I wear him on my sleeve. The jumpsuits and half capes pretty much give it away. So, like I said, being a Lifestyle Elvis is not the same as being an Elvis impersonator. Impersonating is performing. Lifestyling is more like abiding by the code of the 4-H or the Boy Scouts.

My turn-off was coming up so I shifted my attention back to the highway. Blink doing 75 and you can completely miss the unpaved lanes that pass for roads out here. Not this one, though. The exit off Interstate 80 was marked with a large wooden sign cut in the shape of a pork rind. “Pritchard Rind Ranch” was spelled out inside a circle of flaking black paint, with a picture of a happy cartoon pig eating pork rinds in the center.

I hit the brakes and stared at that sign.

Pritchard Pork Rinds are legendary in the Elvis community. Both because Vernon Pritchard, the reclusive owner of the company, is rumored to be a Lifestyler himself and because they were Elvis’s favorite brand. Buddy always had a case of them in the cab of his eighteen-wheeler, despite his fervid dislike for all things pork. No bacon, no ham, no chops. It was the one thing about Elvis he just couldn’t relate to. He was always trying to get me to take a bag or two of the things when he came to see me and my momma, but the idea of eating fried pig skin is about as appealing to me as downing a lard sundae.

I didn’t know what the relationship between Phil, Pritchard Pork Rinds, and Buddy was, but seeing that sign brought back memories of the conversation that had driven us apart a year ago.

Buddy believes that Elvis is still alive and living under the name Jon Burrows. For all I know he’s right. But Buddy’d taken me on my first Burrows hunt when I was a teenager and I’d grown tired of following up on leads that went nowhere. Eighteen years of looking and Jon Burrows was still a ghost. The up side was that I’d developed a talent for detective work and our efforts had resulted in a nice side business for Buddy, buying and selling Elvis memorabilia. After my last assignment, checking on a lounge singer in Cincinnati that might have been Elvis and wasn’t, I told Buddy I was done. We fought. It was bad. He hung up. And that was it for a year, until he reached out to have me get dirt on Phil.

As much as I wanted to see Buddy again, I didn’t want to get pulled back into the search for Elvis. I thought about turning around, decided against it, and stepped on the gas. Besides, I wanted to know what Pritchard Pork Rinds had to do with a dick in a vintage Camaro.

Chapter Two

I turned off the highway onto a gravel access road. After a few miles, I came upon an electric fence penning in flocks of large, fuzzy, ostrichlike birds. They were pacing back and forth, letting out booming honks as I passed.

My drive finally came to an end at a large circular parking area closed off on three sides by a rustic wooden fence. A grand maple tree stood to one side of the circle, and I parked my Ford under its shady arms.

The red Camaro from the night before was parked across the circle from me. Several ranch hands were busy rubbing terrycloth towels over its spotless surface. Phil sat beneath a smaller maple directing their efforts from the shady comfort of his deck chair.

“Dry it faster! Come on! I don’t want water spots!”

I got out of my car and Phil stopped barking commands long enough to squint at me suspiciously. Then he rose from his chair, chest puffed out like one of those weird birds I’d passed on the way in, and bellowed at the help.

“Hey! Don’t use the dirty towels! You’ll scratch the finish!”

Alpha male status firmly established, Phil thrust his chin in my direction and grunted loudly in greeting.

I nodded back.

Asshole.

The screen door at the front of the house opened with a squeak of old hinges. An ancient-looking Mexican woman in a brightly colored skirt and blouse stepped out with what appeared to be a tall glass of iced lemonade. Her arms were thin and frail looking, but she held the glass steady as a rock.

“Good morning!” she said with a smile and a heavy, familiar accent. “I am Louisa.”

This was evidently the woman I’d spoken to on the phone.

“It’s very nice to meet you Louisa, I’m—”

“Señor Floyd. I know. Buddy is expecting you. That is a lovely jumpsuit you are wearing.”

Compliments on my apparel, although always appreciated, are fairly unusual the first time I meet someone. The fact that Louisa didn’t bat an eye at me must have been Buddy’s influence.

This jumpsuit—although it’s really more of an ensemble—is one of my favorites. It’s called the “Black Fireworks Suit,” and the black pants, black sash, and black jacket are adorned with gold sequins arranged in starbursts and arcing contrails. The patterns really do look like fireworks on a summer night. The sash has a large, gold-colored oval where the belt buckle would be, and gold chains coming from the sides and around the waist. A sequined black half cape with a crimson lining ties it all together.

“It’s a replica of one Elvis wore on the ’71 national tour,” I told her.

“Well you’re simply dashing in it, Señor Floyd. Would you like a nice drink to cool you down?”

“I’d love one,” I admitted, and accepted the sweaty glass from her.

Phil saw the lemonade in my hand and yelled out, “Hey, Lucy, bring me a glass of that, will you?”

I took a sip. It was perfect. Icy cold, not too tart, not too sweet.

“Did you hear something, Señor Floyd? The wind I think,” Louisa said in a voice loud enough for Phil to hear.

I decided I liked her very much.

She continued to ignore Phil’s calls for lemonade and disappeared back into the cool darkness of the house with a curt “come with me.” The old springs on the screen door pulled it closed with a bang behind me.

The foyer of the Pritchard Ranch had wood-paneled walls hung with oil paintings. I stopped to admire an abstract portrait of a chubby naked woman. “Picasso” was scrawled in the lower corner. The one next to it I can only describe as some sort of astral wedding ceremony. It was signed “Chagall.”

Louisa watched me examine the paintings.

“Are these—?” I asked.

She just smiled and said, “Investments. This way, Señor Floyd.”

At the end of the hall was a sunken living room with a spectacular view of the back half of the Pritchard estate. Pork rinds had obviously been a very lucrative business.

“When did you last see Buddy?” Louisa asked me.

“It’s been a while,” I admitted.

She patted my cheek.

“Go down the hall. He’s in the room on the right. Try not to get him too excited, okay?”

I knocked on the door she’d pointed to.

“Come in,” I heard Buddy say.

I let myself into an infirmary. Complex medical equipment mounted to the walls monitored Buddy’s pulse, blood pressure and who knows what else. Buddy was sitting in a hospital bed with a book in his lap and an IV line running from under his collar to a bag hanging from a pole behind the bed. More IV bags filled a rack of stainless-steel shelves.

The last time I had seen Buddy he’d looked fine. A bit thin, but fine. He’d lost at least half his weight since then. His normally ruddy, clean-shaven face was gaunt, pale and covered with patchy stubble. White crud had built up in the corners of his mouth

, and his lips were dry and cracked. The kind brown eyes were the same, though.

“It is good to see you again, boy,” Buddy said.

His voice was raspy and thick, like he had a sore throat.

“What’s going on?” I asked, still trying to understand what I was looking at.

“I got liver cancer, Floyd.”

“How long?” I asked, stunned.

“How long I had it, or how long I got left?”

“Both, I guess.”

“I’ve known for six months,” Buddy told me. “Doc says I’m about done. Could be days. Could be weeks. But not longer. Tumors are all over my body, in my guts, my lungs, eating me up.” He paused and frowned. “Don’t look at me that way, boy. Like Elvis said, ‘Ain’t nothing you can do about death and taxes.’ Now pull up a chair and let’s have a chat.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked, sitting down next to him.

“You’ve lost enough people already. Didn’t want you burdened with this.”

“I’m sorry. About our fight,” I said. “I wish you would have called me sooner.”

“Me too, boy,” he said wearily.

I sat, looking at him, not knowing what to say. Elvis had brought us together and then driven us apart. Elvis was big on forgiveness, though, so I had always believed Buddy and I would make amends. I just didn’t think it would be to say goodbye.

“Hey, you see them crazy birds?” he asked finally.

“Yeah, I did. Ostriches?”

“Uh-uh. Emus. Guess they make good eating, but I wouldn’t know. They crap all over the place. Practically wallow in it.” Then, to himself, he added, “Worse than pigs. Don’t know how the hell Elvis could eat those things.”

There was another moment of awkward silence while the two of us struggled for something other than Buddy’s cancer to talk about.

“Did I ever tell you about the time I met Him?” he asked. His eyes sparkled with anticipation. It was his favorite story, and he had told it to me. Dozens of times. And he knew it.

“No, I don’t think so,” I said.

Buddy looked up at the ceiling, closed his eyes, and remembered.

“This was November, ’77,” he began. “I still owned the guitar shop in Boise. Elvis had just died a few months before. Your dad had passed, too. You would have been eight then?”

“Six,” I corrected him.

“That’s right. And already dressing up like Elvis. Boy that made your momma happy. My heart just wasn’t in it anymore, so I decided to close the store. I’d sold almost everything when a fella in a white suit and Panama hat came in. Told me his name was Jon Burrows, and he was looking for a Gibson Dove. I had one. In fact, it was just like the one Elvis used on tour. That six-string had the darkest ebony finish you ever saw. I even lacquered a Kenpo badge next to the bridge the same way Elvis had done. Your dad used to play that Gibson for you and your mom and sing Elvis tunes. I think that’s why she liked seeing her little man dressed up.”

Buddy stopped his story to cough and pointed to a glass of water sitting just out of his reach on the nightstand.

“Give me a little of that, would ya?”

I held the glass for him as he sipped from the straw.

“Thanks,” he said, motioning the glass away. “The cancer drugs make me thirsty as hell but I can’t hardly keep anything down. Anyway, this fella took one look at that Gibson and said to me, ‘Buddy, you got to let me buy that guitar.’ Problem was, that’s the only one I wouldn’t sell. I wanted you to have it when you got older. So I apologized to this fella that he couldn’t have it and told him about you and your dad. He thought about that, then told me to hold on a minute while he got something out of his car. I was afraid he was going to come back in with a gun.”

Buddy usually punctuated this story with a laugh when he mentioned the gun, but it was another burst of coughing that interrupted it this time. I gave him some more water and when his hacking settled down, he continued.

“The fella came back with a roll of hundred dollar bills and a photograph. He put that roll on my counter and said, ‘Buddy, there’s five grand.’ Then he set the picture down beside it. It was an autographed photo of Elvis with a note beneath the signature. You know what it said?”

“What did the note say, Buddy?” I asked on cue.

He smiled.

“It said, ‘Obey your momma, live a clean life, and do what’s right for you as long as it don’t hurt no one.’ Then the fella looked me in the eye and said, ‘Sounds to me like that boy could use Elvis’s advice and his momma could use the money. And I sure could use that guitar. What do you say?’

“Well I thought about it. He was right. About you and your mom. So I handed over the Gibson and he held it like an old friend. I picked up the roll of cash and slipped off the rubber band to count it, thanking the fella on his way out. He stopped in the doorway, guitar in hand, and looked over his shoulder at me. That’s when I knew it was him. But even if I didn’t know it then, I would have in a minute, ’cause this fella, he said to me, ‘No Buddy. Thank you. Thank you very much.’ Then he was gone. Like a puff of smoke.” Buddy nodded his head, satisfied with the end to his story.

“Elvis did not die on a toilet,” he said with conviction. “He is alive and well.”

I’ve been listening to Buddy tell this story almost my entire life. I don’t doubt that a guy really did come in and buy a Gibson. I’m just not sure it was Elvis. What I do know is that day set Buddy on a new path. He closed the shop, bought a big-rig truck and hauled freight all over the country, looking for the man in the Panama hat. The fact that Jon Burrows was the name Elvis used during his performing days when he didn’t want his fans, or the press, beating down his hotel room doors just added to Buddy’s sureness.

I’ve never understood why Buddy wanted to find Elvis. If the man wanted to fake his death, who were we to look for him? But I loved Buddy like a father, so I helped him. Until I just couldn’t anymore. I realized now that the cost of walking away from his quest was too high. I couldn’t undo that decision, but I could try to make up for it by staying by Buddy’s side until the end.

“You do what I asked you?” Buddy said.

“I did.” I patted the envelope of photographs in the breast pocket of my jumpsuit. “But why are you here and not in a hospital?”

“’Cause I hate hospitals,” Buddy said. “And because there are two things left I want to do before my time on this good green Earth is done.”

“And they are?”

“You meet Vernon yet?”

“No.”

“Turn around, boy.”

A woman was standing in the doorway behind me, looking at Buddy with a small, sad smile.

Her hair was as black as midnight and fell to either side of her pale, pretty face. Bright red lipstick played up her full lips. She was wearing a deep purple velvet jumpsuit with a collar that rose up to her ears and a neckline that dipped down to her navel. Gold chains held the front of the jumpsuit together, revealing everything without revealing anything. Another gold chain was cinched around her waist and the legs of the suit were tucked into high-heeled, rhinestone boots.

I knew there were some lady Lifestyle Elvises out there, but it didn’t occur to me they might suit up. Vernon managed to both look the part and still come across as all woman.

Her gaze shifted from Buddy to me.

“You’re staring,” she said.

“Sorry. You’re Vernon Pritchard? I thought you were an old man.”

She let out little snort. “It’s a long story.”

I was about to ask to hear it when Buddy started coughing again. It was worse this time. The cough racked his body, and Buddy rolled onto his side, his hands grasping at his chest as he struggled for breath. Bloody foam began to dribble from the corne

r of his mouth. Vernon’s forehead wrinkled in concern and she pushed me out of the way to check on him.

Buddy’s face had flushed a bright red and the strain of the coughing made the veins in his neck and face swell and pulse.

“You haven’t been using the morphine,” she said, pressing a button on a box attached to the IV stand.

“I’m not sleeping away my last days, girl,” Buddy sputtered as his spasms subsided.

Buddy had never married and had no children of his own. If I’d been the son he never had, Vernon was clearly the daughter. As she adjusted the flow on the IV, Buddy watched her with the same affection I’d seen in his face when he used to take me out for ice cream on hot Saturday afternoons.

I suddenly felt hurt that he’d never told me about her.

“We should let Buddy rest,” Vernon told me, wiping the blood from his chin. “I just gave him a bolus of morphine. It’s nap time.”

“Not yet,” Buddy objected. “Floyd, I still got two things left to do! The photos...for Vernon. She’ll tell...tell you...the other.”

Buddy’s eyes closed and his breathing deepened. He was asleep.

Vernon brushed a wispy lock of hair off of Buddy’s forehead and pulled the covers up around him.

“Why don’t you go wait in my study,” she said. “Go through the double doors in the living room. I’m just going to make sure Buddy’s comfortable and that his meds are ready. I’ll join you in a minute.”

I nodded and slipped out of Buddy’s sickroom. Vernon had a nice house, and she was obviously rich, but nothing could have prepared me for what was behind the two heavy wooden doors leading to her “study.”

Chapter Three

I stood in the doorway, my mouth hanging open like an idiot. Study was the wrong name for the room. Museum would have been better. Crossing the threshold was like stepping into a shrine to Elvis.

A perfectly preserved 1968 baby blue Cadillac convertible with white leather seats sat dead center. Elvis loved cars, and once called the ’68 Caddy as close to perfect as any car can get. I could see why.

Elvis Sightings (An Elvis Sightings Mystery)

Elvis Sightings (An Elvis Sightings Mystery)